Beefy birthday

CSU pioneer in cattle feeding turns 100 story by Coleman Cornelius published Jan. 13, 2021In 1936, when he was 15 years old, Johnny Matsushima raised his first Hereford steer as a 4-H project and showed it at the Weld County Fair in Greeley. He was showing alongside a younger 4-H rival named Kenny Monfort, whose family was already well-established in the Colorado beef industry.

Monfort had the grand champion steer at the fair that year. But Matsushima had an idea: He took his steer back to his family’s farm south of Greeley. He fed it a bit longer, hauled the animal to auction at the Denver Stockyards, and fetched top dollar.

Editor’s note: The original version of this story appeared in CSU news outlets in 2013, when John Matsushima was named Citizen of the West.

It was his first step toward an influential career in the science of beef-cattle nutrition, statewide and nationwide. Colorado ranks No. 4 in the country based on cattle on feed, with well over a million animals munching their way to market – on rations developed with the innovations of a diminutive son of Japanese immigrants, who recently turned 100 years old.

In fact, Matsushima’s evolution into a foremost nutrition scientist helped fuel the arc of Monfort’s own career as a captain of the nation’s cattle-feeding and beef-packing industry; years after their county fair steer shows, the two were friends and research collaborators. Their partnership and others like it helped grow the cattle business into the heavyweight sector of Colorado’s agricultural industry, which annually contributes an estimated $41 billion to the state economy.

“I don’t think Colorado would be a top cattle-feeding state if it weren’t for Johnny’s work,” said Daryl Tatum, a retired professor in Colorado State University’s Department of Animal Sciences. Tatum is among many scientists who have advanced Matsushima’s studies linking beef-cattle nutrition and management practices to animal welfare, meat quality, and producer profits. “Johnny did as much as anybody in teaching and research to elevate the commercial cattle-feeding industry in Colorado and elsewhere. He was a game-changer.”

Celebrating 100 years

Matsushima celebrated his 100th birthday on Dec. 24, 2020. Friends with the Rotary Club of Fort Collins feted him with a birthday parade. Photo: Matsushima family

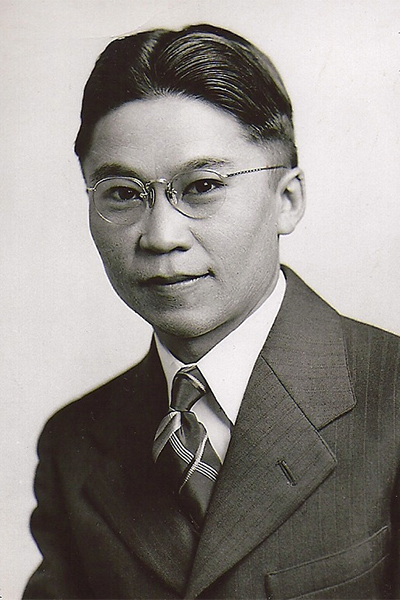

Matsushima grew up on the family truck farm in Platteville and attended Colorado A&M, now Colorado State University, to earn a bachelor’s degree in animal husbandry in 1943 and a master’s degree in animal nutrition in 1945. He later worked as an educator and researcher at CSU for more than 30 years and, even now, he maintains close ties to the university as a professor emeritus.

His friends and colleagues rekindled their appreciation for Matsushima as he celebrated his 100th birthday on Dec. 24. Although he has been mostly homebound during the COVID-19 pandemic, Matsushima remains healthy and closely connected to his family with the help of video calls. He continues to live in his longtime Fort Collins home with support from his daughter, Nancy, and regular physical therapy. He often walks, now using a cane, at a nearby park for exercise and fresh air and, in the summertime, spends time in his rose garden.

“I feel good,” he said during a recent FaceTime phone chat, with his trademark cheerful smile. He had just received his first dose of COVID-19 vaccine, which offered hope for the year ahead.

On the bright and chilly morning of his birthday, Matsushima sat bundled in a lawn chair in his front yard to receive socially distanced greetings from dozens of longtime friends from the Rotary Club of Fort Collins who drove by, honking, waving, and calling out their best wishes. The club also formally honored Matsushima for his civic service; he hasn’t missed a single weekly meeting during 52 years of club membership, even as the group has convened virtually during the pandemic.

Video by Savannah Waggoner

On campus, CSU Athletics recognized Matsushima on the massive scoreboard at Canvas Stadium: “Happy birthday, John! Thanks for being our longest-standing season ticket holder and Ram Club member,” the message read, also noting Matsushima’s role as co-founder of Nutrien Ag Day, an annual game-day barbecue during football season. Fort Collins Mayor Wade Troxell proclaimed Dec. 24, 2020, “John Matsushima Day” in the city and highlighted the honoree’s motto, “Learn from the good things, forget the bad.” Friends sent more than 260 birthday cards.

Also marking Matsushima’s birthday, the Colorado Livestock Association and Colorado Cattlemen’s Association presented him with an engraved crystal award for innovations that have spurred the cattle industry, one of many similar honors he has collected over the years. Matsushima was named 2013 Citizen of the West by the National Western Stock Show, a prestigious annual award that recognizes those who embody the spirit of the West and perpetuate its agricultural heritage and ideals, and has been inducted into 4-H and FFA halls of fame. He also was named one of CSU’s Best Teachers in 2002 and accepted the 2003 William E. Morgan Alumni Achievement Award, the CSU Alumni Association’s highest honor.

A giant in the livestock industry

Matsushima started and served as superintendent of the Fed Beef Contest at the National Western Stock Show for two decades. He is seated next to his late wife, Dorothy, during one of his family’s many visits to the annual livestock show in Denver. Photo: Matsushima family

Some of the most telling evidence of Matsushima’s work is tucked inside metal filing cabinets in his living room. Here, he still keeps meticulously typewritten grades and class records, amassed while teaching an estimated 10,000 students, many of whom went on to their own notable careers in agriculture. Within these manila folders is the name of Bill Hammerich, now chief executive officer of the Colorado Livestock Association, who took Matsushima’s Feeds and Feeding class as a student in 1968.

“If his globally recognized accomplishments weren’t enough, Dr. Matsushima is doing something that very few of us will likely get to enjoy, and that is to celebrate our 100th birthday,” Hammerich said. “We have all heard the word ‘giant’ used to describe those who have contributed in a positive way to an industry or a cause for the betterment of mankind. Even though he is small in stature, Dr. Matsushima is a true giant in the livestock industry. His vision, passion, and curiosity are all qualities that enabled him to move the cattle industry forward for the better part of a century.”

Beef-cattle feeding – yielding greater efficiency, carcass quality, and profits – was Matsushima’s expertise as an educator and researcher. His innovations helped modernize and expand U.S. beef production with scientific underpinnings, data-based decision making, and global reach.

In 2019, Americans consumed an average of 58 pounds of beef per person, based on retail weight, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Beef consumption has dropped in the United States over the past several decades, essentially swapping places with chicken as the favored animal protein among Americans. Yet, with some ups and downs, the nation’s beef exports have notably climbed during that time. That makes cattle production the most economically important agricultural industry in the United States, according to a recent USDA summary.

The invention of flaked corn

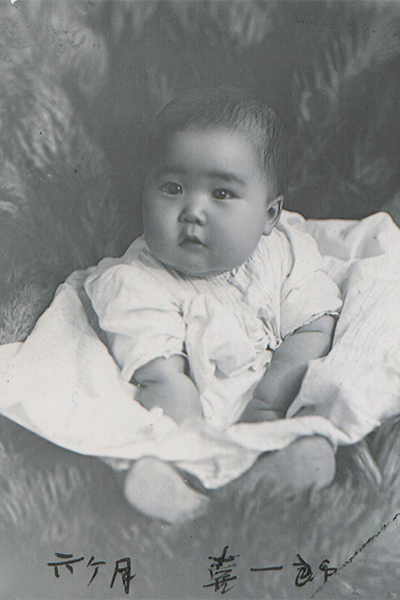

John Matsushima grew up on his family farm in Platteville, south of Greeley, Colorado, and raised Hereford steers as a member of 4-H and FFA. Photo: Matsushima family

As cattle feedlots were expanding across the state and nation in the 1960s, Matsushima pioneered the process of using steam and mechanical pressure to macerate corn kernels into corn flakes. The process makes starch more digestible in a cow’s four-chambered stomach, thus improving feed efficiency by about 10%, reducing the amount of grain needed in feedlot rations and improving profit margins. The innovation remains a cornerstone of global cattle feeding.

“Efficiency has never been more important than it is today,” said Randy Blach, a former Matsushima student and chief executive officer of CattleFax, which provides industry analysis. “The technology he developed nearly 60 years ago has more value today than ever before. That’s phenomenal.”

The late Kenny Monfort, an early adopter of the technology, joked that he flaked more corn than Kellogg’s at his feedlots. “Although researchers at many universities were working on flaking at the same time, I think Johnny’s work was the best and most significant,” Monfort told The Denver Post for a feature published in 1967 about Matsushima, headlined “Genius of the feedlots.” By then, Monfort was assuming leadership of Monfort of Colorado Inc. from his father, Warren, and was helping establish the first 100,000-head cattle feedlot near Greeley. “We thought enough of it that we changed our whole feeding program,” Monfort said of Matsushima’s flaked rations.

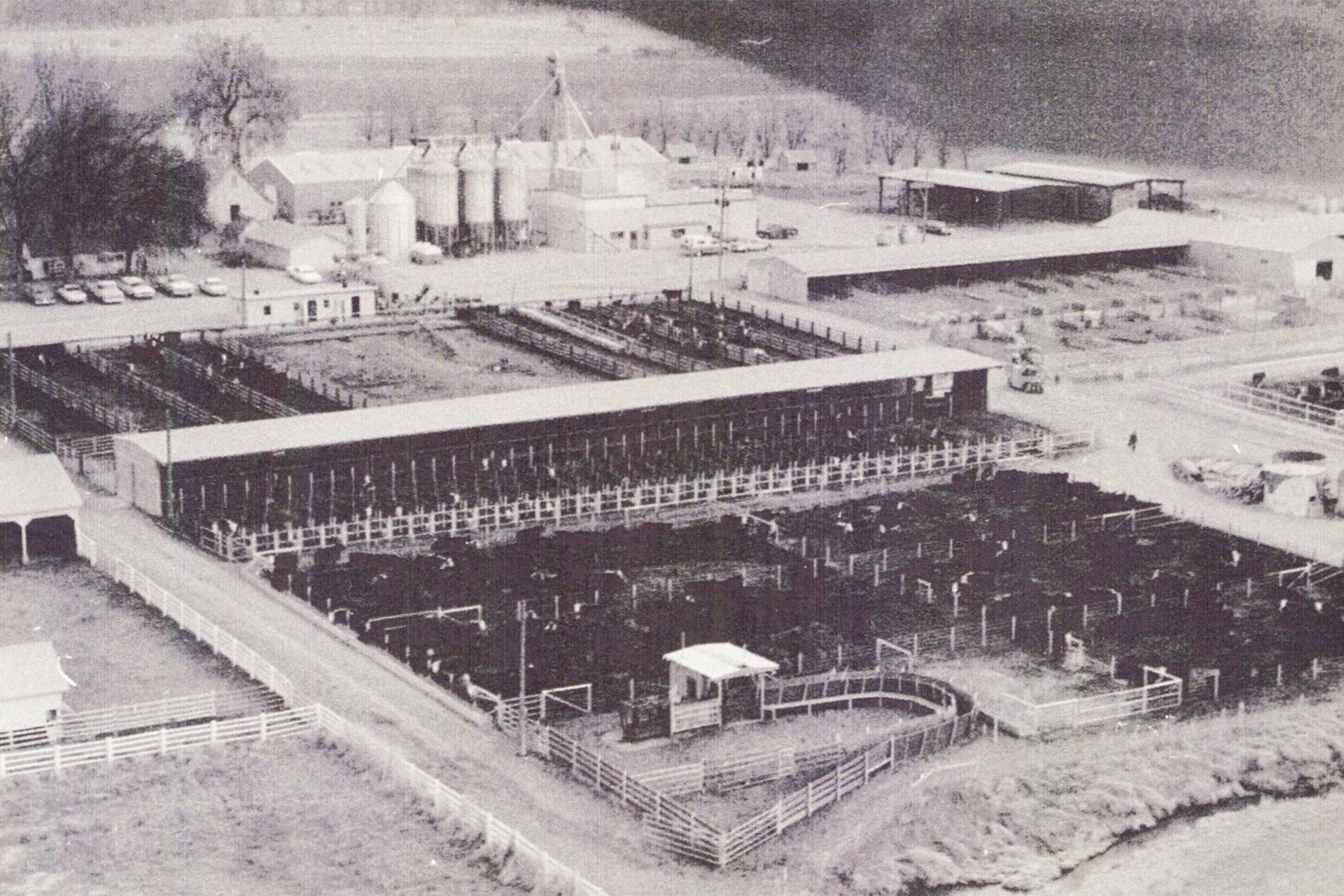

In 1961, Matsushima began his teaching and research career at Colorado State. He conducted beef-cattle nutrition research at CSU’s Rigden Farm off East Drake Road in Fort Collins. Photo: Matsushima family

As a CSU researcher, Matsushima obsessively monitored the amount of feed that cattle had consumed – or left behind – in bunks at the College of Agricultural Sciences’ old Rigden Farm on the east side of Fort Collins, where the scientist conducted nutrition trials and jotted observations in daily record books. It was part of pinpointing technologies and rations that increased weight gain and decreased time to market. And he didn’t stop at feed: Matsushima helped develop equipment widely used to stir and serve feedlot grain rations.

The start of modern nutrition

Matsushima’s big idea sparked on a frigid morning in 1961. He was eating a breakfast of hot cereal with some cattle feeders when it hit him: Maybe hot grain would appeal to feedlot cattle. The idea launched his research in steam-flaked feed grains – and the notion that rations could be served warm.

“He’s one of the pioneers who started developing modern cattle-feeding procedures,” said Paul Clayton, vice president of food safety and quality assurance for Seaboard Triumph Foods and another former student. “Innovation was one of the things we were really pressed to work on at CSU. He motivated us to think about problems in a different way.”

Several years ago, Matsushima visited the Kuner Feedlot, a 100,000-head feedyard built by Monfort of Colorado east of Greeley; it’s now owned by Five Rivers Cattle Feeding. The feedyard was a familiar stop during the 1970s and ’80s, as he worked with large feeders to perfect research discoveries for practical industry application. Matsushima took the information he learned there to develop rations used by cattle producers around the world. “After all, food is a big issue in many countries, and beef is the choice of animal protein,” he said.

A long way from his beginning

It was a long way from Matsushima’s beginning to his standing as an industry pioneer. He credits his late wife, Dorothy, their children Bob and Nancy, and other family members, friends, and colleagues for supporting his tireless work and travels.

Matsushima was born to Japanese immigrants at Mercy Hospital in Denver. He was named Kiichiro and lived his early years in what he describes in his autobiography as a wooden shack near Lafayette. His cradle was an apple crate.

His family spoke only Japanese, and when Kiichiro arrived for first grade at Davidson School in Boulder County his teacher was confounded by the language difference. Rather than learning how to pronounce the boy’s given name, the teacher nicknamed him “Johnny.” It stuck.

The Matsushima family was poor. But his parents, who had eight children, saved $4,200 cash at the outset of the Great Depression and bought an 80-acre irrigated vegetable farm near Platteville. They focused on farm work, and as an adolescent Matsushima began contributing to family income by trapping and skinning muskrats, then selling the pelts for up to $2 each. He used some of the money to buy dairy calves, which he raised and sold for more profit. His family later kept a small herd of Hereford cattle.

He advanced to officer positions in 4-H and FFA and used income from his livestock projects, combined with scholarships earned for graduating as valedictorian of his class at Platteville High, to attend college.

It was a struggle financially. Matsushima worked his way through school and wore the same shoes for two years, patching them with cardboard and rubber from a local tire shop. After earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees at CSU, he was recruited to the University of Minnesota for doctoral studies in the fledgling field of beef nutrition; his dissertation reported fattening performance of feedlot steers. It was Matsushima’s launching pad for teaching and research.

Japanese heritage drew bigotry

World War II was underway as Matsushima studied in Fort Collins, and his college life changed dramatically when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. It didn’t matter that he was born and raised in Colorado; Matsushima’s Japanese heritage drew bigotry.

Local grocery stores hung signs ordering that “Japs Stay Out.” Matsushima and his roommates, also Japanese American, couldn’t buy food. So a fellow member of the livestock judging team bought their groceries and delivered them to Matsushima’s basement apartment in the dark of night. Matsushima was banned from a Fort Collins movie theater while out with the judging team, was refused a lift home in a snowstorm, and was denied membership in an academic honors fraternity.

The indignities eventually waned. Matsushima finished his schooling with a growing passion for teaching and research in feeds and feeding. His first job was at the University of Nebraska, where his findings in beef-cattle nutrition got the attention of area cattle feeders. These included the prominent Weld County cattleman Warren Monfort – Kenny’s father — who was spearheading a novel approach to year-round cattle feeding with crop surpluses.

The elder Monfort encouraged Matsushima to return to Colorado State, where he was hired in 1961 with the promise of a research facility that could annually handle more than 3,500 beef cattle and an appointment that included working with the Colorado Cattle Feeders Association to understand and solve problems. The site of that facility, Rigden Farm, is now a housing subdivision on the east side of Fort Collins.

As Matsushima’s reputation expanded, he became a seminal figure in opening Japan as a market for U.S. beef exports. Central to this role were his technical knowledge, cultural proficiency, and language skills, which he had improved with childhood lessons at Japanese summer school.

“Dr. Matsushima’s heritage was a big benefit,” Clayton, formerly with the U.S. Meat Export Federation, observed. “The fact that he was able to get markets to open and give the U.S. the ability to have access to foreign markets is very big, and getting those markets open was very, very difficult. That’s a milepost of his career.”

Crowning achievement

Matsushima has said his crowning achievement was earning the Japanese Emperor Citation, or “Tenno Hosho,” presented in 2009 by Emperor Akihito at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. The award typically is given only to national dignitaries and corporate leaders. Matsushima was honored for promoting quality beef in Japan, for innovating steam flaking of corn, and for teaching some 10,000 animal science students at three universities. It was “perhaps the happiest day of my life,” Matsushima writes in his autobiography. Recalling this work, the CSU Department of Animal Sciences sent Matsushima and his family Wagyu steaks for his 100th birthday dinner.

Matsushima formally retired from CSU in 1992, but with his emeritus professor status has maintained an office in the Animal Sciences Building. Before the pandemic hit, he regularly visited to check mail and phone messages. “He calls me several times a year and wants updates on data,” Blach, of CattleFax, said. “That tells you it never has been a job for him. He has a passion for the industry.”

Matsushima explained his ongoing quest to gain and share information: “Knowledge never goes out of season.”